A Painting Lesson from a Volcano

At the 2016 Colby College RESCUE sale—an annual yard-sale event of stuff students left behind at the end of the school year—I came across a Ziploc bag full of tubes of acrylic artist’s paint. I asked a volunteer, “How much?” Five dollars. Sold. The bag held about 20 tubes of barely used acrylics. My wife asked why I bought them—after all, she reminded me, you don’t paint. I replied, “I do now.” However, before I got a chance to try out the paints, we left for a two-week trip to Sicily for a wedding. When we returned, images of Sicily filled my head. I pulled out the paints and subsequently created four variations of one of my favorite scenes.

In Sicily, we stayed in Taormina, just north of Mt. Etna, Europe’s largest, most active volcano. The volcano dominates the landscape of eastern Sicily. The town of Taormina is picturesquely situated on a steep hillside overlooking the Mediterranean. All those rusty red-tiled roofs, craggy hills, deep blue of the sea, and clouds constantly forming and dissipating around Etna provided plenty of elements for an interesting painting. How do I start? I’ve dabbled a bit in watercolors, but acrylics are a totally different beast. So I decided to do a few sketches first, to get the lay of the land. Or was drawing just a way of procrastinating before I opened the paint and made a fool of myself?

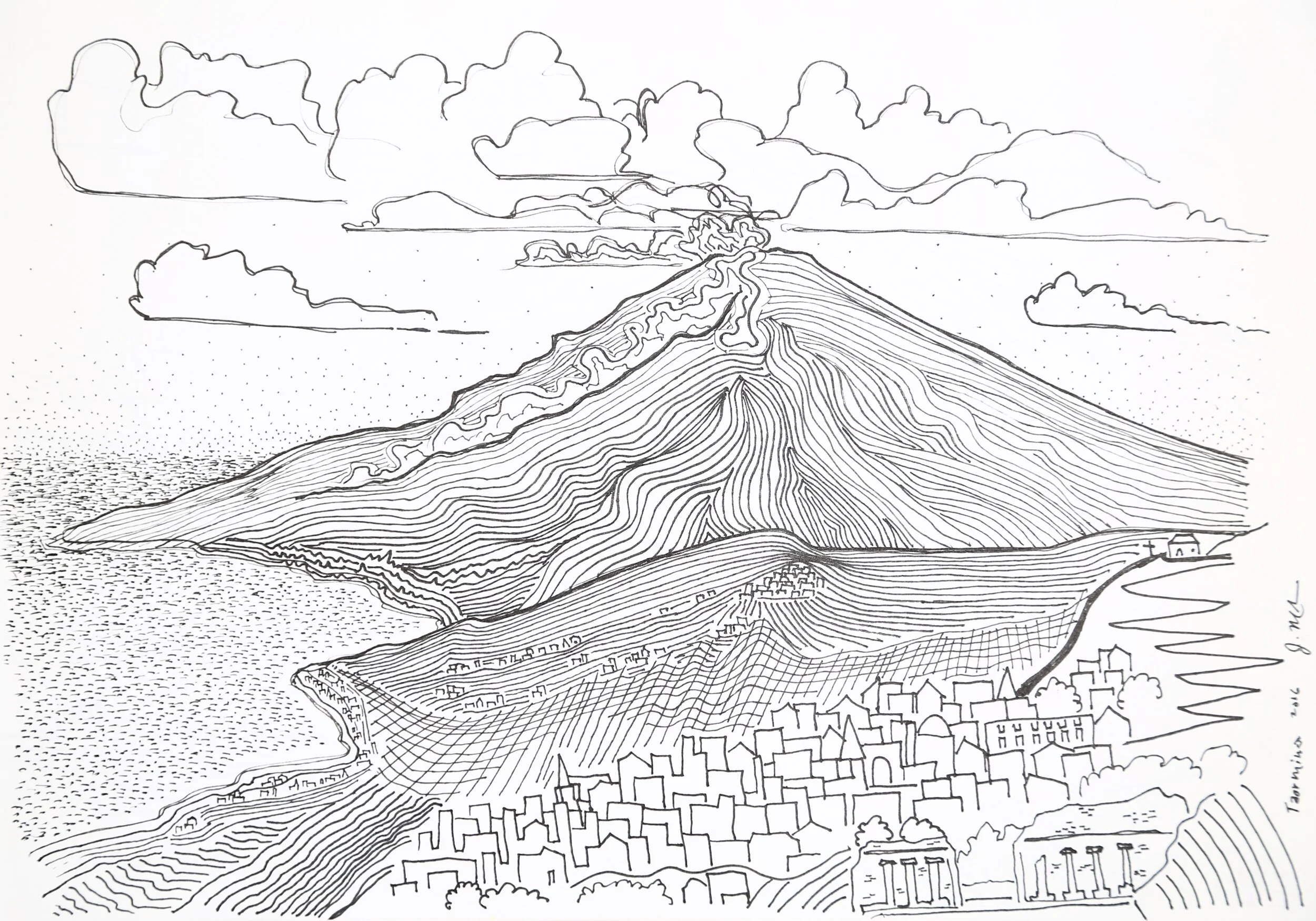

Etna and Taormina, ink on paper.

Trying to make a simple line drawing to capture the juxtaposition of the organic volcano versus the structured forms of the ancient Sicilian town, complete with the Greek theater in the foreground, I came up with this ink drawing. After several sketches, this one was a keeper.

The one aspect of Etna that was the most dynamic and fascinating to me was the sky, specifically the clouds. The volcano always seemed to be enveloped in clouds with fog (or perhaps steam?) tumbling out of it. The impression was that this nearly 11,000-foot mountain was creating much of its own weather. Then on our second or third day in Taormina an amazing cloud formation formed just downwind of Etna’s summit.

The Flying Saucer Cloud

This giant cloud lasted all day, constantly changing yet retaining its basic form, slowly undulating and shifting as if were alive. Clouds like this are called lenticular clouds. They are created by moist stable air flowing over a mountain or range of peaks, then the moisture condenses just downwind of the mountains. I took lots of photos. I knew that this cloud would be in my first painting.

It was time to paint. I bought a pre-made canvas and gessoed it. Gesso is a thick white acrylic that fills the canvas, giving a better surface on which to paint. Sketching out the basic forms, I started laying down color.

The volcano and the clouds started to take form, then the Mediterranean, and finally Taormina. I wanted to keep it simple—let the essence of the place and the sky speak rather than get lost in detail. Ah, that is the crux: getting lost in detail. How much detail to put into the village? Do you add windows and doors? Do you add window frames and doorknobs? How about trees? Plants? Flowers? Where and when do you stop, and when do the details take over and the essence is lost? Remember, this is my first acrylic painting ever. The good news is that once I got over being gun-shy, I started to have fun. It turns out that acrylics are very forgiving. If you do something you really don’t like, let it dry—that takes about 10 minutes—then paint over it! In the end, I liked the painting, but I did what I set out not to do: I got lost in the details.

Taormina and Etna #1.

I was happy for the most part with this painting. I liked the town and the volcano, but I worried about the flying saucer cloud. I wondered what others might think when they saw it. And that’s exactly what happened. “Is that the tip of a wing?” “What is that—an overhanging cliff? “Is that an alien spaceship?” Unless they saw my original photograph, people had a tough time interpreting the big cloud. So I decided I should paint another version. This time, I would let the flying saucer cloud go, and just work up some dynamic clouds around Etna.

Taormina and Etna #2

This is my second attempt at this scene. I purposefully painted it quickly, trying to simplify the detail, adding energy instead. Sometimes when I draw quickly, I capture something deeper than the surface detail that I so easily get lost in. This painting from start to finish was done in a couple of hours. I finished it and immediately saw more I could do, but I stopped myself. Let it be what it is. The only thing I added was my signature.

My cousin Abbott Meader, an accomplished artist and retired art professor, looked at the two paintings and, pointed out things he liked in both, while making suggestions about perspective and the use of color. Then he commented on my clouds and atmosphere. He liked the clouds but suggested that I work on the depth that air creates. Atmosphere changes perspective. Distance can be emphasized by adding a sense of moisture and thin clouds. Atmosphere applied well can create mystery, applied poorly it creates mud. I thought about that a lot. So I went back to my photography and studied the air around Etna.

Etna in clouds

Clouds seemed to form over and around the volcano, constantly creating a veil around the mountain, sometimes translucent, sometimes opaque. Always interesting.

I decided to try again, a third painting with more atmosphere, but I just couldn’t get it right. Clouds were easy, atmosphere was hard. I felt this was the weakest version thus far. I like difficult, I like a challenge, but I also like to feel I’m gaining. Here, I felt like I was slipping, and it was only my third painting.

Taormina and Etna #3

The clouds took over. Teaching myself how to paint was beginning to show the limits of my knowledge. There are many good reasons to take lessons, like not having to reinvent the wheel. Here, I was trying to discover how to make the paint more translucent, so I added white—that’s not how you do it. White actually adds opacity to paint. Duh. I needed to do some reading, consult my painting friends and family, and perhaps even watch instructional YouTube videos (god forbid!).

So I was frustrated. I had let go of the detail of the town, only to replace it with the detail in the clouds. Way too much cloud detail. I should put it away for a while. But I couldn’t let it go, not yet. So I tried other sketches, working on simplicity. Maybe I need to be less conventional. What if I drew the scene with just simple straight lines?

Taormina and Edna in Lines, ink on paper

It was kind of funky, but I kind of liked the idea. What can you convey with simple lines? How might this translate into paint?

So I decided to paint the scene in a more simplistic way, perhaps with shapes rather than lines. Shapes are easier than lines with paint, at least for me.

Taormina and Etna #4

I finally made something with a more simplistic structure. I liked the town and the mountain, but I felt the sky is just okay. I know, I’m my own worst critic. Some have said it looks like it’s not done. It is done, and it’s okay that people may think otherwise. I was getting closer to the simplicity I was after. Mainly, I knew I was learning, and that was most important of all.

In the end, I like Taormina and Etna #1 the best of the four, but I had to paint all four of them to learn some things about painting. I’m glad I made them all. But there was still one more image swimming around in my head.

Mt. Etna is an active volcano. I wanted to see it erupt, in at least a small way. I wanted to see lava, though it’s probably best that we didn’t. The sense that the Earth is alive and active is always in the back of your mind when you’re near a volcano. We hired two guides to take us up onto the mountain.

Visiting Mount Etna

We visited 25-year-old lava flows, spelunked into a lava tube, and climbed the rim of an old side vent. We heard stories about past eruptions, a bit of the science of vulcanology, and the lore of Vulcan from Greco-Roman mythology. I also recalled tales of Pele from my visit to Hawaii. I knew that below our feet was magma, and it’s not that far away. Vulcan or Pele, whomever you attribute such events to, could take us out at a moments notice. Remember Pompeii?

This all led me to think about the link between the explosive geology that creates this alien landscape and the way the human spirit has interpreted it through the ages. The Greek Hephaestus and the Roman Vulcan were both personified with the powerful masculine smithy ethos whose heat and fire allowed civilization to forge iron. To the Hawaiians, it was the female Pele, the creator of land, known for her immense power, deep passion, and capricious jealousy. Etna was quiet during our visit, although it has since erupted in 2017, 2019, and 2020. What if these far-flung gods should occasionally meet up? The energy would certainly erupt with all the passion and energy the Earth can produce. Thus came my final painting, the first in which I painted a human form, also my first nude. It arose from the desire to see an eruption balanced with the knowledge that perhaps I shouldn’t really be close enough to see it. A sense of voyeurism, looking in on the passions of a Vulcan and Pele rendezvous, a most dangerous perspective.

When Vulcan and Pele Meet